“Cezanne’s famous damning praise, ‘Monet is only an eye, but what an eye!’ had such impact that it killed interest in Monet’s heart or mind.” (Jackie Wullschlager Monet the Restless Vision)

Great set design addresses more than the visual. “Ultimately what it looks like is important, but getting there you need to know what it means,” Beowulf Boritt tells me. His mind and heart have made themselves known in over 31 Broadway shows the past 15 years and more than 489 across the globe since he began.

Therese Raquin – The Apartment: Keira Knightley and Matt Ryan

One example is the oppressive browns and golds of Therese Raquin (2015) whose claustrophobic apartment and actively churning river epitomize the loveless marriage of Zola’s heroine. For Come From Away (2017): “I knew that people who lost people would come see the piece,” Boritt remarks. “Telling a real story to victims made me want it to be real stuff. The back wall was made of real wood we weathered by sandblasting it with broken glass. It makes the grain more prominent. And I wanted real trees, not Styrofoam or plastic. Our scenery shop found a lumberjack in the Catskills. I went up into the mountains with him and tagged 24 trees. We sealed up the bottom so the water didn’t leak out.” In April the trees onstage miraculously started sprouting leaves.

Come From Away – The Company

Drafting a Designer

Beowulf Borritt was born to a Pulitzer Prize nominated American Civil War scholar and an aspiring singer. The house was full of Asian art collected while his father worked abroad. He believes it had subliminal influence on what became a less decorative approach to design. “My favorite building in the world is The Pantheon in Rome. That simple geometric shape and use of space,” he pauses. “But then I also love the Chrysler Building.”

Mom was in a volunteer chorus at the Memphis Opera. At eight or nine, she’d take him to dress rehearsals. Boritt remembers being flummoxed watching a stage hand push a 20-foot boulder across the stage. He smiles. His grandmother had been an art history major at Wellesley. She made scenery for the college drama club and excelled at fashion design. It was she who gifted Boritt with his first set of paints, lavished him with encouragement, and along with his mother, taught him to sew.

There were no art lessons. On his own, he experimented with mediums. Dioramas were built with blocks, Legos and clay appendages stuck to Playmobile figures. “I’ve always been into more sculptural stuff,” he says. “I don’t use 2D on my stage if I can help it.” His parents cleared a bottom shelf in the den where the boy switched out scenes. The Lord of the Rings books were particular favorites to manifest. “I think that’s what interests me in the theater. At its heart it’s a person saying words to another person.”

Another nascent skill was woodworking. His mother is a trained cabinetmaker, his grandfather was accomplished. Several family houses were renovated. At a very young age, Boritt was allowed to use hammers, saws, and power tools. “There was a sense in my family that if you needed something made, you made it,” he says.

Beowulf Boritt, 2005

When school plays were an option, he acted, acquiring an appreciation for theater. It was during a season of summer stock at Gettysburg College he met a scenic designer professor and realized the craft was an actual job. Returning to Gettysburg High School, Boritt enthusiastically volunteered to make the next year’s sets. For the musical Cinderella he ambitiously built a coach “out of 2x4s and a lot of rope patterns glued on and painted gold.” It had wheels, a 2D horse and was big enough to ride in.

Vassar followed. The drama syllabus was “basically a literature course,” he says. “I took some acting, built a few sets, and wrote my thesis. The plan was to teach scenic design, but my girlfriend, now wife, Mimi Bilinski, said she didn’t want me to be an academic.” He moved to New York and attended NYU Graduate School. That entire first year was spent on paper projects. Boritt tells me he thought he’d go out of his mind. Answering an ad, the young man designed costumes, then a set in the South Bronx. “In the early nineties getting to and from Arthur Avenue I was sure I’d be killed,” he says.

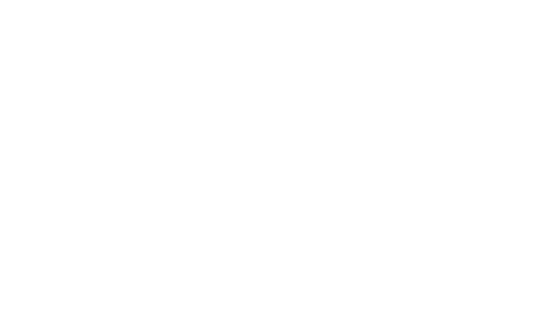

Costumes – Left: for Titus Andronicus; Right: for Turandot

Professor Eduardo Siacanco, whose work was “frilly; lots of swirly lines, lace, frou-frou,” encouraged Boritt to be more decorative. “I liked him, but resisted because I wanted to do something conceptual and serious. Eduardo said, ‘Just because it’s pretty, doesn’t mean it doesn’t have an idea behind it.’ I learned how to approach embellished design from a conceptual angle. My bread and butter is musicals these days and very much influenced by that.”

After graduation, he did some adjunct teaching between design jobs, but when offered a full time position in Pennsylvania, “Mimi put her foot down. If he was going to BE a set designer…” She echoed one of two pieces of early advice by which he lives: Take the financial hit if necessary but work at what you do – i.e. don’t drive a cab or wait on tables.

“I did a downtown play about an Italian family fighting with each other,” he says. “It was one of the first times I encountered a pushy playwright and a director who wouldn’t stand up to him.” The designer built a big, awkward looking house neither he nor the director could stand. Two days before the first preview, Boritt came in early, went up on a cherry pickier lift and “smashed my way through it knocking holes in the entire set. I hung the broken part kind of crookedly above it. Cheap 1970s paneling was easy to break.”

“It looked fantastic,” he pauses. “It was a play about an unhappy family. I was venting, but it also solved a problem and turned out to be a good lesson. More of my sets than I can name have been askew. Drama tends to be about things askew/broken, so I frequently mirror that in some way in the visual.”

Hamlet in Central Park

Boritt designed four shows for Kenny Leon. The director’s Much Ado About Nothing in Central Park was seen through a political fisheye. Taking place in contemporary Georgia, it featured a large Stacy Abrams for Governor sign. Hamlet, which followed, was consciously set a year later. Leon suggested to Boritt that the production should be “turned on its side” visually indicating social upheaval and environmental issues. The Abrams sign returned cast off on the lawn; a jeep was abandoned in receding water, Kronberg Castle was notably askew.

Beowulf Boritt and Kenny Leon in Tech

“Breaking something looks more like a broken thing than a scenically designed broken thing…” If he wants something weathered and worn, the designer will go at it with a baseball bat, chisel, and hammer. Today he’s carrying a bat gifted him by carpenters during a Public Theater production in 2019. (He finally broke the first one.) It has “Grendel Basher” carved into it somewhere beneath the dents and gouges.

For Prince of Broadway (2017), Tevye’s cart (Fiddler on the Roof) received this treatment on the sidewalk of 47th Street. Boritt then splashed it with dirty paint washes and amber shellac. He drew a crowd, some of who volunteered to help. The garbage cans and even pianos in New York, New York (2023) were similarly beaten up. “The upside is that Local One stage crew is amused,” he chortles.

Tevye’s cart; “Aging” a dressing room table for Harmony

“Hal (Prince) and James (Lapine) were like fathers to me.”

Eminent scenic designer Ming Cho Lee organized something called Clam Bake, an open exhibition at The Lincoln Center Library to which every graduate school in the country sent designers. Each student got a table and a bulletin board. “It was like a coming out party. Producers, designers and directors would attend.” (When Lee died, alas this ended. These days there are local events, but nothing national.)

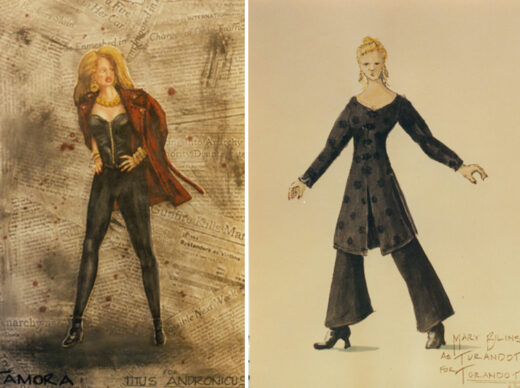

Hal Prince made it a point to go to everybody’s stall. “There must’ve been 60 or 70 students,” Boritt notes. The legendary producer/director took a resume from everyone so no one would feel left out. The ones he liked went into the right pocket, others into the left. Back at the office, he wrote each hopeful designer saying it was nice to meet you, thanks for sharing your work.

Boritt showed an intricate model of Love’s Labour Lost including an intricate Elizabethan tree house. (They existed.) The set stood on an electronic turn table. “Hal pushed the button and was delighted. He loved things like that,” he tenderly reflects. Using Prince’s letter as an excuse to stay in touch, the young man wrote every six months or so.

His pro-action exemplifies a second credo: “What’s normal and polite behavior in the rest of the world is not enough in the theater. You have to be a bigger personality, a pushier person, more dramatic – or get ignored…I was a wallflower in those days. I watched people around me and taught myself to do it. It doesn’t come naturally. A lot of creatives who get ahead are the same way…”

LoveMusik

Several years later, Prince asked him to design LoveMusik (2005) about Lotte Lenya and Kurt Weill. He rejected the young man’s first concepts. Taking a risk, Boritt suggested painting the entire stage bright red. “It pushed us into a more theatrical world. The first scene was Lenya rowing a boat across the stage to Weill on a dock, but the floor was bright red so clearly you’re not in the real world. I thought either he’s gonna love it or he’s gonna fire me.” Prince loved it. “I use a lot of black on stage, but red is a go-to for passion, for extreme feeling.”

The two also worked together on Paradise Found (2020) based on a Joseph Roth novel at Menier Chocolate Factory in London. “It was poorly produced and perhaps not a very good piece,” he comments. “I was trying to do a Hal Prince Broadway show in a small space. We designed too much scenery. Hal’s memory of the tech was me standing on stage screaming, “Fuck this fucking, fucked, fuckhead theater!”

Hal Prince and Beowulf Boritt (Photo: Dan Kutner)

“Hal was a force of nature. I first started working with him in my thirties. You walk into his office and the history of the Twentieth Century is on the wall. It’s overwhelming. He was a bulldozer. He never hesitated. If he was wrong, he’d just change it days later. As we worked together more and more I realized just because he said it didn’t mean we had to do it and it didn’t mean he was right…I miss him in a thousand ways.”

In 2005, The Putnam County Spelling Bee moved from Barrington Stage to Second Stage Theater. “I remember reading the script and thinking, this is stupid, adults playing children…” Boritt’s agent talked him into it. James Lapine directed the New York production. Charles Isherwood then of The New York Times wrote, “Beowulf Boritt invests an antiseptic space with cheesy warmth.” Lapine and the designer worked together on three more Broadway shows.

Putnam County Spelling Bee (Photo: Joan Marcus)

“James is prickly, quieter than Hal. He can get very frustrated. Hal stayed in charge by yelling and screaming. James does it by keeping everyone off balance. When I was young that was hard to deal with. Now it just washes off. It’s a technique. I love the man dearly. It’s like your father or brother giving you shit. I’ve had a real artistic meeting of the minds with James.”

James Lapine and Beowulf Boritt (Photo: Jack Shear)

“He’s intelligent and calm, very chill, unflappable,” Lapine tells me about Boritt. “I’m not the easiest person to work with. I can make people flappable …I’m not a social guy, but what we do is very intimate. Projects are all consuming, often with a gun at your head…It’s like making a baby.”

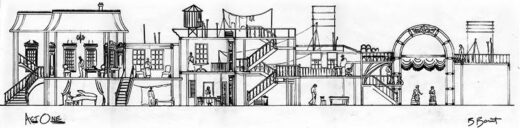

The Model for Act One

At the start of working on Moss Hart’s autobiographical Act One (2014 – written and directed by Lapine), Lapine said, “I have an image of a young man trying to break into the business, running up and down stairs, banging on doors.” Boritt’s three-story set on a giant turntable offered lots of stairs and doors and according to him, “not much else.” “Hal used to say, ‘Everyone will imagine his own wallpaper,’” the designer quotes. (Boritt earned the Tony Award – Best Scenic Design for a Play.)

Act One: Santino Fontana, Andrea Martin, and Tony Shalhoub

Boritt also designed Lapine’s Flying Over Sunset (2021) “It should be somebody’s brain on drugs,” Lapine advised of the unusual piece of historical fiction. “I thought, let me make a big circular space. Our brains are kind of round. LSD fucks with your perception of things,” Boritt comments. When Botticelli’s The Return of Judith to Bethulia comes to life in a Rexall Drug Store meant to look like the perfume floor at Saks, we know we’re not in Kansas anymore. Simulating depth and movement, a marvelous ocean scene used so much dry ice it “fell into” the audience. Small fans were surreptitiously placed to blow it off. Critic Marilyn Stasio called it “trippy.”

Flying Over Sunset: Michele Ragusa, Kanisha Marie Feliciano, Laura Shoop, Harry Hadden-Paton, and Robert Sella

Flying Over Sunset

All uncredited photos: Beowulf Boritt